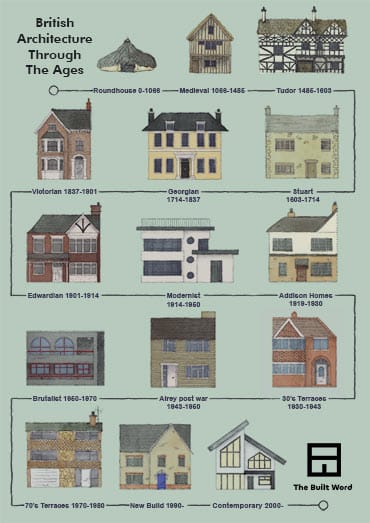

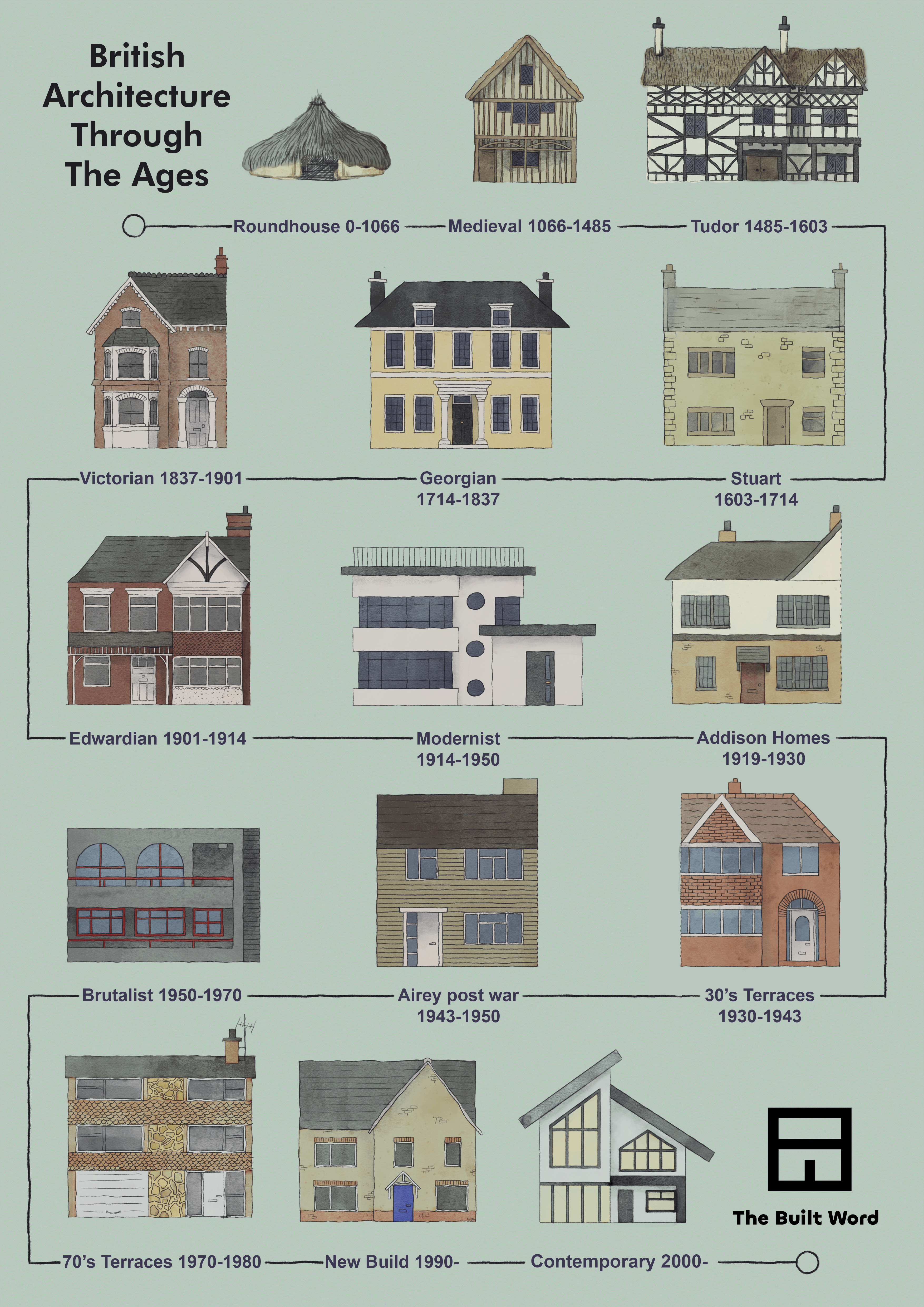

Free illustrated cheat sheet poster at the bottom!

Ever wandered what your house says about English history? Find out how our politics shaped each architectural style and discover the long and unique history of English architectural styles.

Starting with vernacular mud huts and moving through to today’s contemporary designs, it’s easy to lose track of what came when; so here’s a clear, illustrated timeline to guide you!

Instead of including a smoke hole or chimney (which would have risked igniting the thatch) the design allowed smoke from the central fire to rise and collect near the roof. There, families hung fish and meat to cure. Gradually, the smoke leaked out through the thatch, which in turn created a protective coating against pests and mould.

In terms of scale, roundhouses measured anywhere from five to fifteen meters in diameter, though they typically appeared in clusters rather than standing alone. Inside, each building consisted of a single room with a central fire pit. Because they lacked purpose-built rooms, people slept, ate, and worked in the same communal space.

Roundhouse -1066

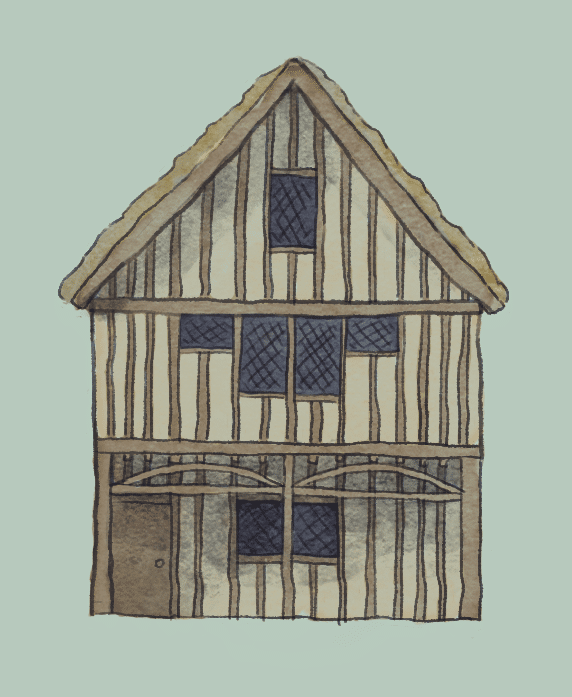

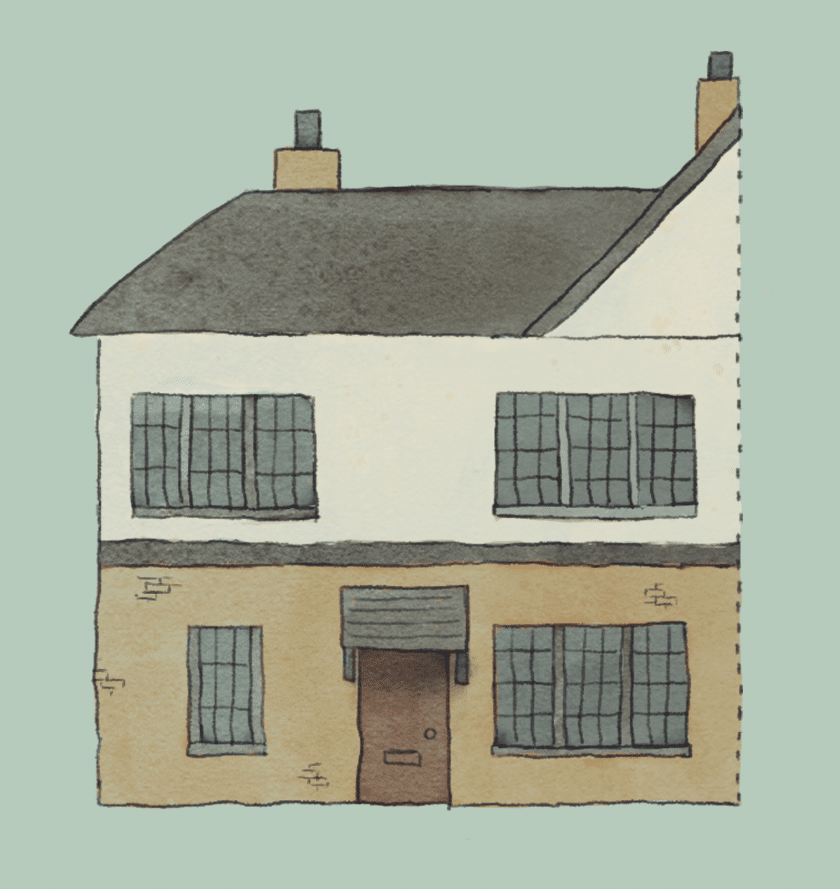

At this stage, domestic architecture began to evolve beyond the single-room layout of roundhouses. Families started incorporating purpose-built spaces such as private chambers and workshops. In doing so, medieval homes came to reflect the feudal system itself. Movement and access within the household were no longer equal but instead reinforced the social hierarchy.

Medieval 1066-1485

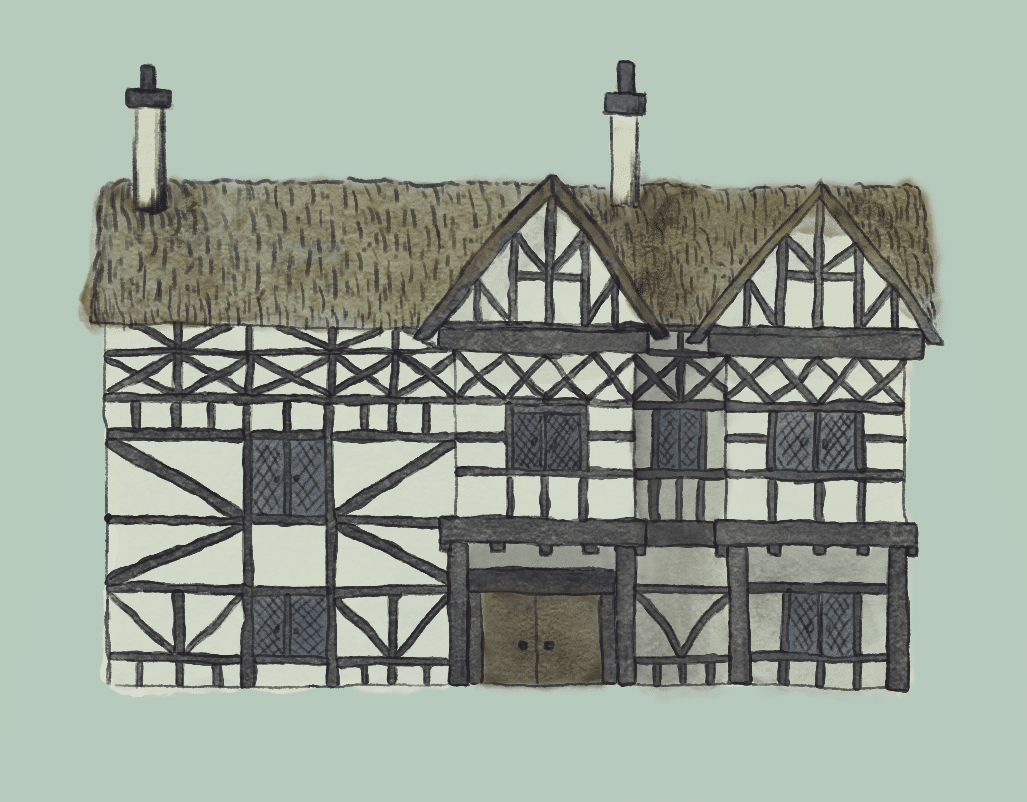

At the same time, Tudor politics left a visible mark on domestic architecture. The Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII released vast amounts of land and building material, which ambitious landowners quickly repurposed for their estates. Tall brick chimneys, announced status by revealing that a household could afford multiple fireplaces.

Thus, Tudor homes embodied more than design trends, they stood as expressions of power, prosperity, and allegiance in a changing England.

Tudor 1485-1603

Inspired by the northern European Renaissance, these great houses featured symmetry, ornate façades, and expansive layouts. Most notably, they displayed vast mullioned windows, a bold statement of wealth at a time when glass remained expensive. Their sheer size and visibility made them impossible to ignore.

Elizabethan

1550-1625

Ordinary families continued to live in modest Tudor-style homes, which changed little during this period despite the flourishing ornamentation of the nobility’s estates.

Jacobean

1603-1625

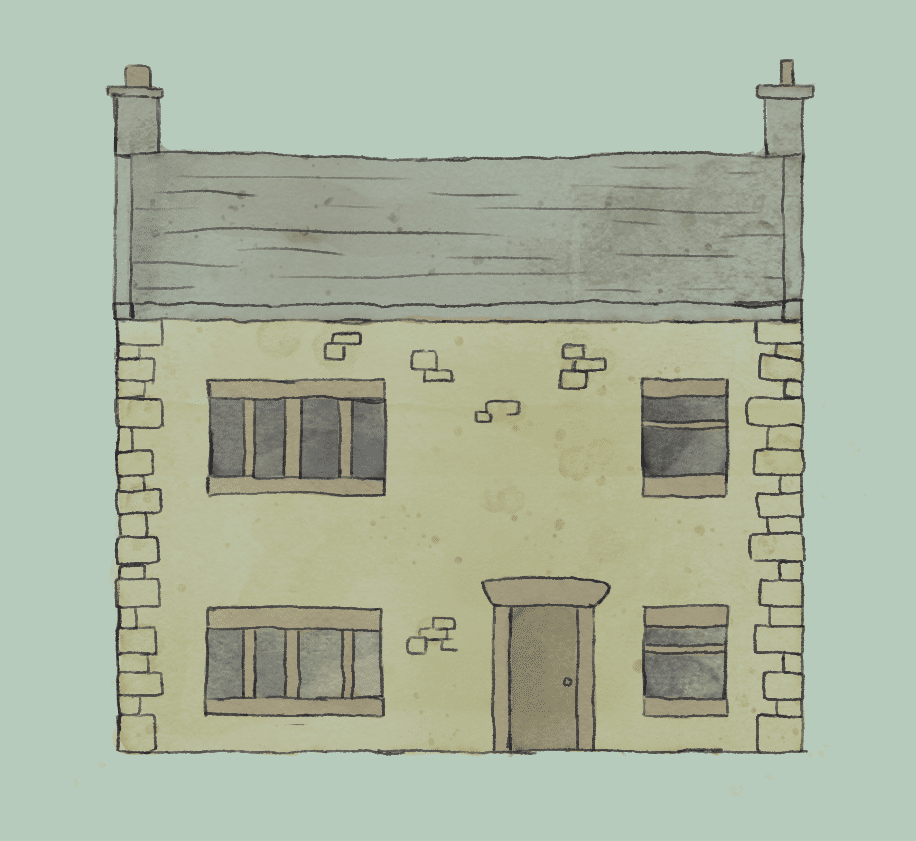

While most couldn’t afford the ornate Renaissance style, they still took classical ideas such as symmetry on a flat fronted facade, ‘E’ shaped plans, and plastered high ceilings. Some even used chimney stacks to resemble classical columns and external cornicing to imitate on a modest budget.

Stuart 1603-1714

While these grand houses belonged to the wealthy, elements of the Queen Anne style gradually filtered down to more modest homes. Ordinary dwellings began to adopt sash windows and symmetrical façades.

Queen Anne

1702-1714

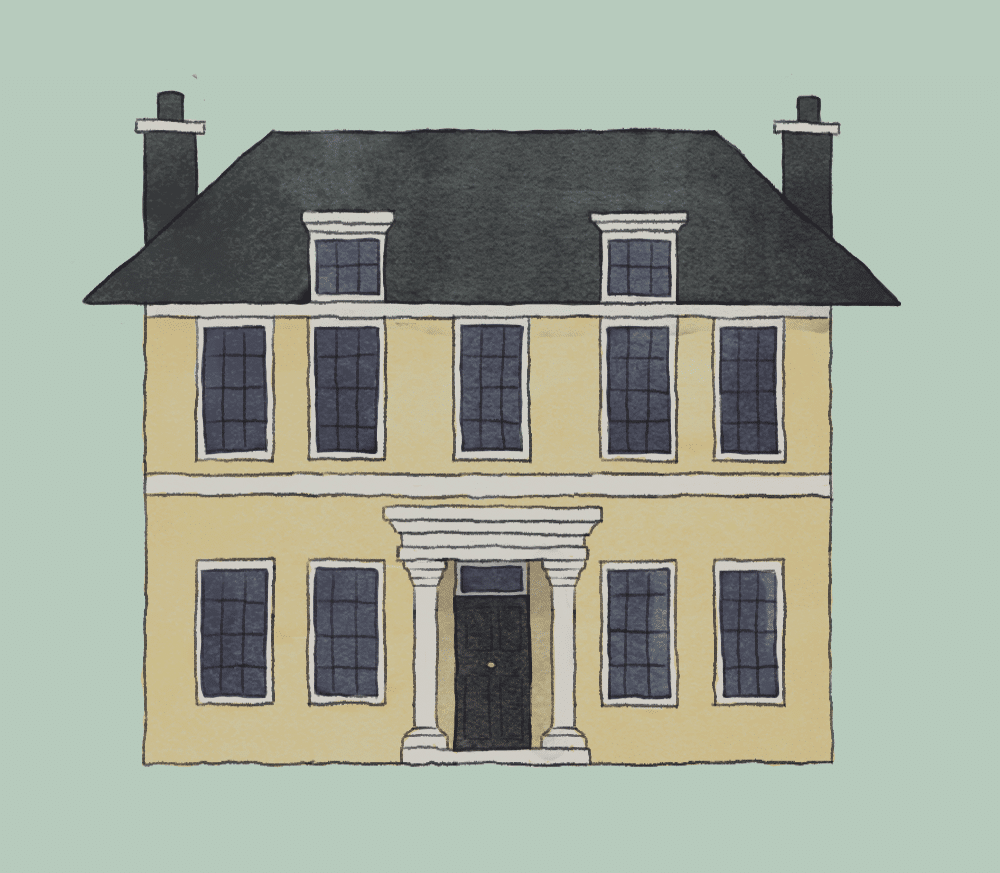

Characteristic features included large porticos, temple-like façades, and other classical motifs set against plain stone walls. The structures were all about proportion and symmetry. However, it was a style reserved for the elite as architects claimed the classic style as ‘pure’ and ‘moral’.

Palladian

1715-1770

They typically had warm toned brick with white detailing. The entrances were grand six paneled doors topped with fanlight windows and framed by columned porches. High ceilings allowed for large double-hung sash windows with 9 or more window panes while dormers on hip roofs became a common feature.

Due to the population boom, terrace houses emerged as a practical solution in cities. These rows of uniform houses combined efficiency with elegance, allowing ordinary families to embrace classical design on a modest scale while creating cohesive, visually harmonious streetscapes.

Georgian 1714-1837

Regency 1811-1837

The signature of the Victorian terrace is the bay window on the downstairs living room, which featured wooden sash windows to provide ventilation for the coal fires. The walls use red bricks and a distinctive white stucco or stone dressings around the windows. Meanwhile, the front doors are timber paneled with glazed upper panels featuring stained glass. It was a mish-mash of revival styles, gothic asymmetric patterns and finials against classical columns all executed by “Arts and Crafts” artisans, creating visually rich façades even for ordinary homes.

Through these terraces, Victorian architecture reflected both the practical needs of a booming urban population and the era’s fascination with craftsmanship, style, and ornamentation.

Victorian 1837-1901

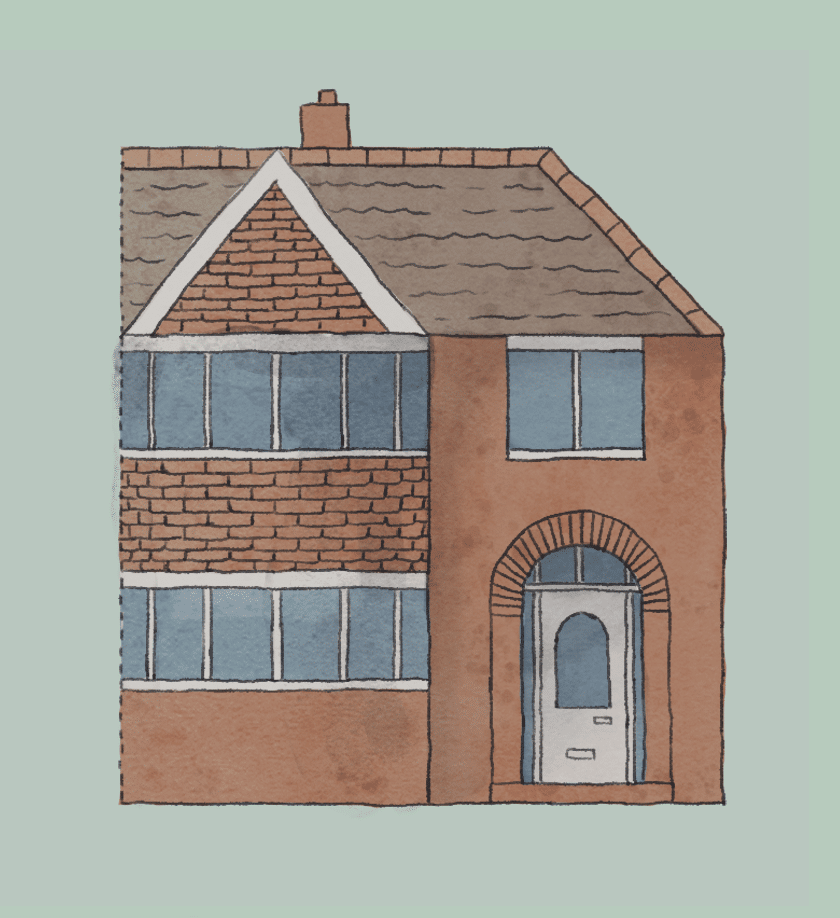

The walls were red brick and could be decorated with pebble dash or mock Tudor white render and black timbering. They often have ornately carved porches over the front door, mock balconies or verandas. The front doors themselves were framed with ornate glazed panels either as a fanlight or transom window above. On the other side would be bay windows stretching over the two or three stories.

Edwardian 1901-1914

Modernist 1914-1950

After the first world war the government set to provide affordable homes for the working class. A promise to return to simple traditional life led to the vision of rural cottages. These semi-detached homes often feature soft warm brick with muted rendering, topped with slate or tile roofing. They borrow the small window panes of yesteryear to add a feeling of history and safety. During these uncertain troubled years Addison homes created a comforting, familiar aesthetic.

Addison Homes 1919-1930

During the 30’s, the UK faced an agricultural depression. Land was cheap to build on, especially near the newly built train lines. This led to a housing boom of new semi-detached homes all over the country. Keeping the idea of history providing comfort, they simplified the Victorian and Edwardian terraces. These houses typically featured curved bay windows, hipped roofs, and recessed porches.

By providing accessible homes on the outskirts of towns and cities, the 1930s terraces reflected both economic necessity and the increasing desire for suburban living.

30’s Terraces 1930-1943

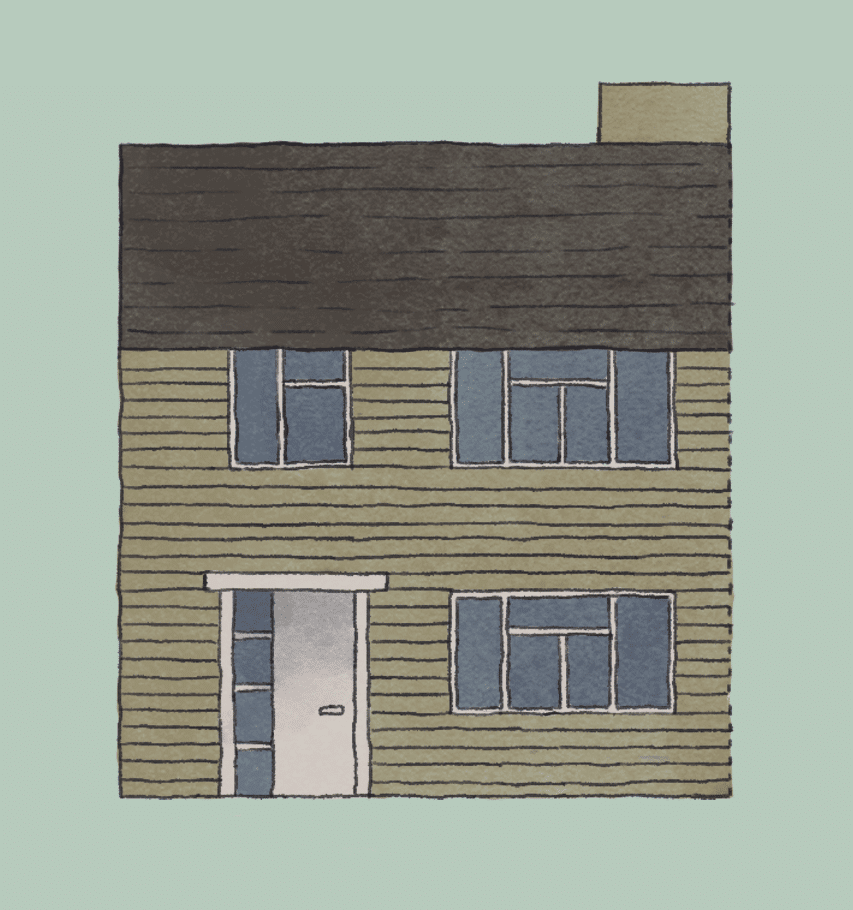

After the Second World War, Sir Edwin Airey designed prefabricated homes to provide mass, affordable housing for a population facing severe material shortages. They have a prefab reinforced concrete frame, with shiplap style concrete panels attached.

Due to the scale of buildings needed and the ongoing material shortage, they were very simple forms with no ornament and small windows. While functional, they weren’t very stable and once the building material shortage was over most were rebuilt, often only retaining the original frame.

Airey Homes 1943-1950

Brutalism is the marmite of architecture, you either love it or hate it. It emerged as a post-war solution for mass social housing. The principals were to keep materials in their raw form, honest construction for honest working class people.

It was a new way to build utilitarian, low-cost social housing usually featuring a lot of concrete in bold interesting forms. Though controversial in appearance, these developments aimed to address urgent housing shortages and offer practical, long-lasting accommodation in the decades following the war.

Brutalist 1950-1970

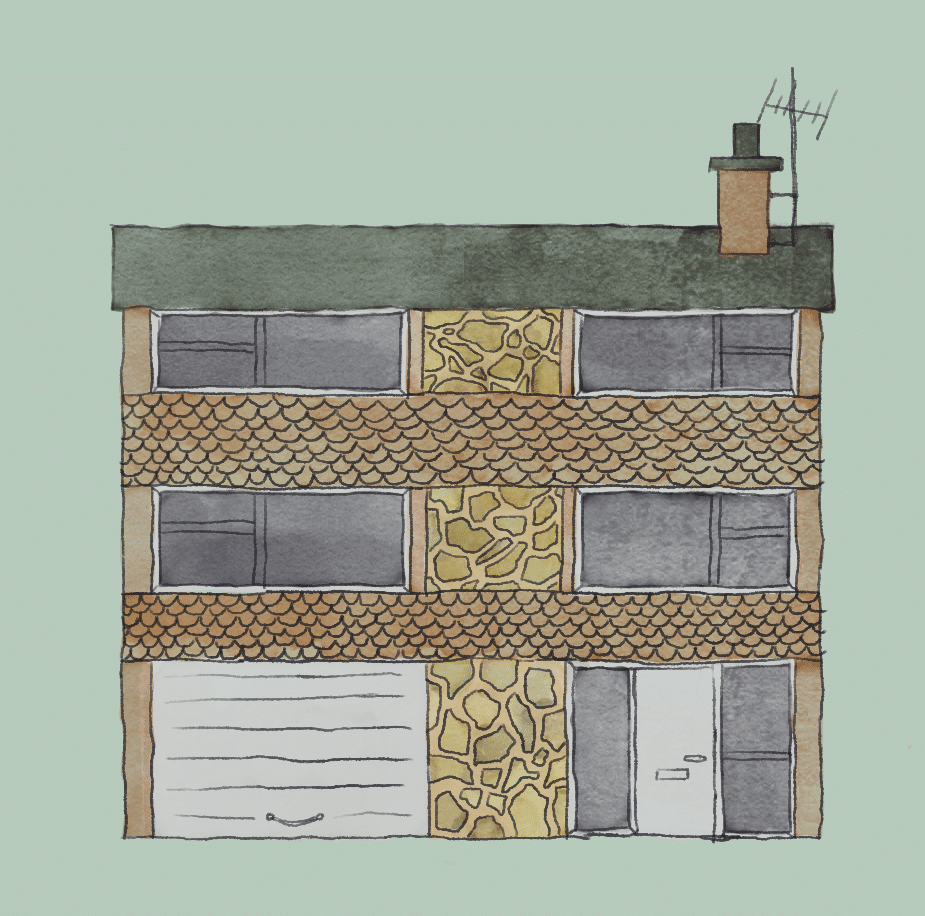

70’s terraces 1970-1980

They use light brown or red brick and are considerably smaller than previous house styles. Often a box shape with a minimal front garden or driveway and an economical back garden. Garages are generally too small for cars, serving instead as storage spaces.

Despite the reduced size, these homes met much higher energy efficiency and safety standards, reflecting modern building regulations and the increasing importance of sustainability.

New Builds 1990-

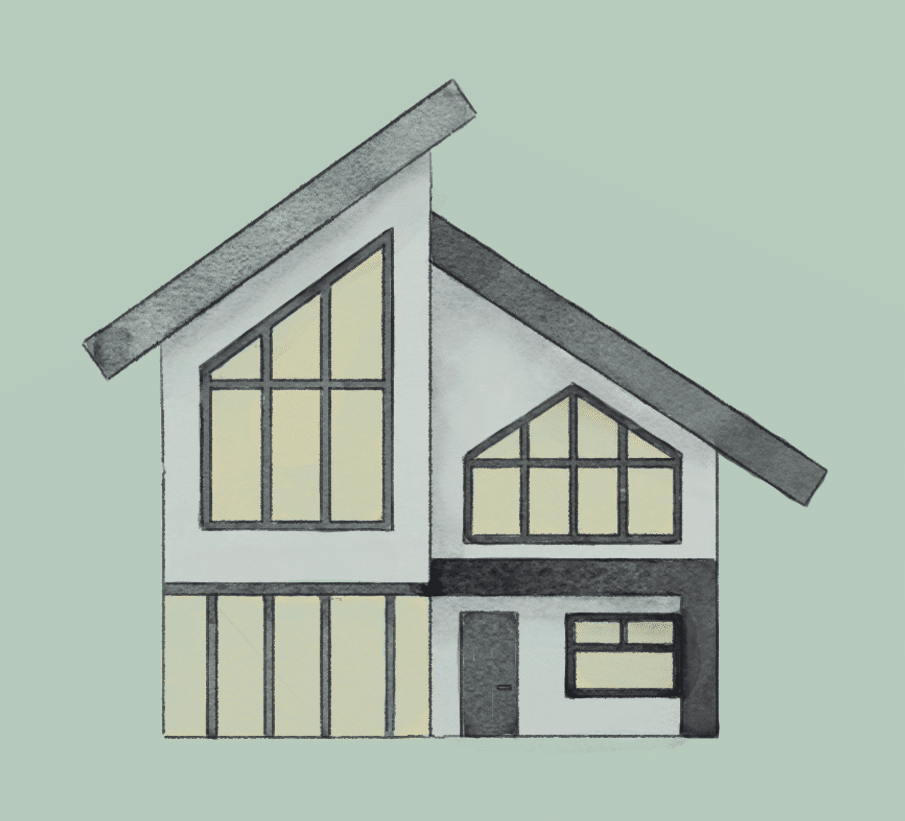

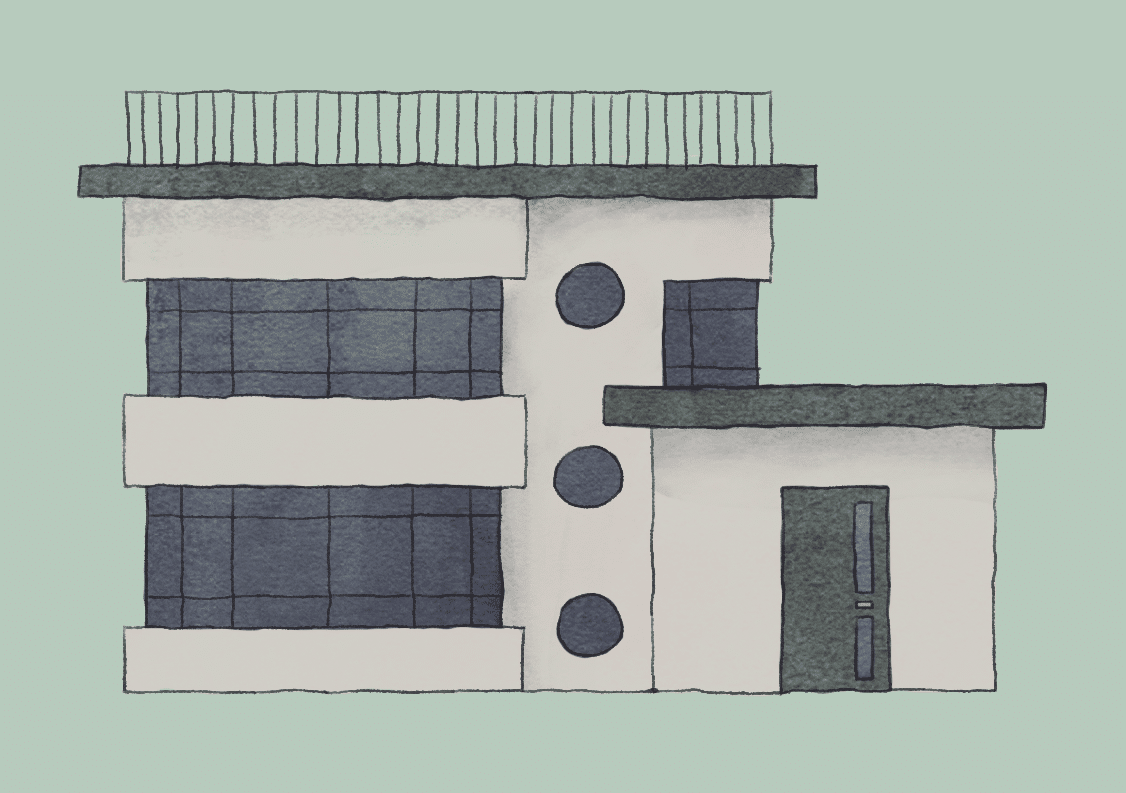

Contemporary middle-class housing often draws inspiration from modernist architecture, emphasizing clean lines, open spaces, and abundant natural light. These middle-class luxe developments have large areas of floor-to-ceiling glazing supported by strong aluminium frames, creating a sleek, minimalist appearance.

Walls are typically rendered or timber clad and doors are oversized in raw construction materials.

These developments prioritize style, energy efficiency, and high-quality materials, reflecting both the aspirations and financial means of the middle-class homeowners who occupy them.

Contemporary 2000-